To Ethiopia, Rediscovering Roots

As with all of ESRA's projects, this one too, started with identifying a need, recruiting a partner, and ensuring the manpower to get it done. The need cried out all too clearly to those involved in work with Israel's Ethiopian community. The children, born in Israel, grow up adopting Israeli ways, Israeli culture, and they must learn it all outside the home, because their parents are not their source of Israeli culture. Their parents grew up with a very different culture, a foreign culture, from which the children distance themselves in order to be Israeli. This puts a strain on parent-child relationships, on respect for parents and elders, and on the normal healthy support system that should be family life. The results can be detrimental, from adversely impacting academic performance, to experiencing difficulties in becoming contributing members of society. ESRA ascertained the need to bridge the gap between these teenagers' Israeli identity and their Ethiopian heritage, to help them develop pride in their heritage, and respect for their parents and the very brave decision they made to come to Israel at all costs – and the costs were great.

Thirteen high school students were selected based on personal interviews, and their journey began eight months prior to boarding the flight to Ethiopia.

They underwent an intensive eight-month course of two hours a week, taught by the Director of the Hefzibah Community Center, Avi Talala. The course was funded by ESRA and the Hefzibah Community Center, both of which subsidized the trip, with the students also contributing to the cost.

In addition to studying Ethiopian history and the story of the Ethiopian Aliyah, the course included an in-depth examination of the students' roots, their Israeli identity, Zionism, leadership and more, and culminated in the trip to Ethiopia. Accompanying the group of thirteen teenagers was their teacher, Avi Talala; Director of the Neot Ganim Community Center, Eliran Moral; and three other adults: Nina Zuck, ESRA Projects Coordinator; Cynthia Yaakobi, a volunteer with Students Build a Community; and myself, Mimi Tanaman, ESRA's volunteer copywriter, with the promise of writing about it. We were honored to have Micha Feldman join us there as our guide. Author of On Wings of Eagles, and fluent in Amharit, one can say that Micha is the true father of the entire Ethiopian Aliyah story.

Day one, we arrive in Addis Ababa and settle into our hotel. Recovering from our 5am start (which is to become more common than we imagined), we have a couple of hours to relax before our evening activity of dinner at a nightclub.

But Avi has something else in store. He informs Nina and me that we will accompany one of the boys to the home of his family, for a first meeting with his 102-year-old grandmother, as well as aunt, uncle and cousins.

After maneuvering through wildly congested traffic, over paved roads, dirt roads, through residential areas and chaotic markets, we finally arrive. A large ornate gate opens into a dark courtyard surrounded by single-story houses. We are ushered into one of them, entering a large room with couches, armchairs and stools. In the corner, leaning on a tiny-screen black and white TV, there is a picture of a beautiful, regal-looking woman – the boy's grandmother when she was younger. And there she is on the couch, now 102 years old, blind and missing some teeth, but still distinguished-looking, graceful. As her grandson bends down to her she utters a squeal of delight, touching his head, his neck, kissing his cheeks, one, the other, the other again, back and forth, and kissing his hands. Nina and I fight back tears at the sight of meeting one's grandson, a big strong boy, for the very first time. His aunt also repeatedly kisses his hands, and his uncle watches with a huge smile on his face, occasionally clapping his hands at the sheer delight of the moment.

We sit together, the boy's hand clasped in his grandmother's, while a younger female family member does the hosting with injira, flat Ethiopian bread used to scoop up the prepared fillings – cabbage and potato, lentils, or a cooked spinach salad. And then comes the traditional buna – a small cup of strong Ethiopian coffee – the requisite feature of hosting guests.

The boy speaks some Amharit. They ask about family members, but mostly they just hold on to him. He gives them what his parents sent for them, and after eating, drinking, and smiling, all accompanied by Avi's fluent Amharit conversation, we finally take our leave with much hand kissing, and his grandmother lets go of the hand of her so recently arrived grandson for the last time.

Making a dramatic emotional switch, we join the rest of our group at the nightclub, filled with music, tourists and food. Amazing Ethiopian dancing had most of the group hopping onto the stage at the end for instruction and dancing with the performers. Then back to the hotel after a very long day.

Day two took us to Lalibella, with its amazing 12th century churches declared a world heritage site. Carved out of rock, the churches took some 20-30,000 people 24 years to complete. We stop along the road to visit a typical rural home – a one-room goji (round hut constructed of wooden sticks covered with a mixture of mud and straw, and topped by a straw roof). The matriarch of the family (the only adult living there with uncounted numbers of children from age 23 to toddlers) welcomes us, and shows us how she grinds her grain into flour on a stone outside her home. Our students have a go. As with everywhere we stop, children seem to materialize out of nowhere and we are surrounded by crowds of them. For just such an occasion, we have all brought gifts to distribute – crayons, markers, stickers. But the children seem most interested in our empty plastic water bottles!

Back at our lodgings in the lovely Tukul Village, we light Chanukah candles in the round, straw-roofed dining room, singing with gusto all the Chanukah songs we can think of, as we did every night while in Ethiopia.

Next morning we visit the Preparatory School of Lalibella, where select students go to prepare for university. Our students enjoy presenting them with gifts of notebooks and markers. And we carry on north to Gondar.

Gondar is the area where most of the Jews who managed to make aliyah had lived. We picnic on a hilltop overlooking a beautiful fertile valley, once cultivated by the area's Jewish villagers. It is now cultivated by others. A small crowd of ragged children appear on the hill and stand watching us. As at every site, Avi explains the significance of where we are, and Micha adds stories. I ask some of the students, "So when you get back, will you thank your parents for leaving, or are you sorry they left this beautiful place, and you'd be one of those children standing there." They answer in unison …"No, no, no, we thank them!"

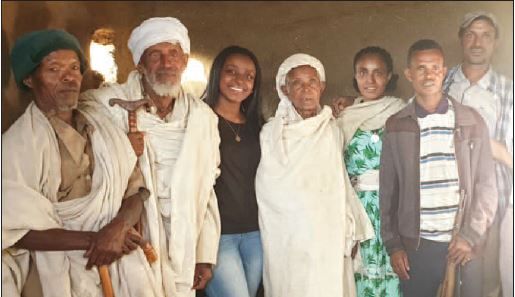

We drive in jeeps over jagged bumpy roads to what used to be a Jewish village, with a school and a synagogue. Both are dangerously crumbling, but new buildings, single-story structures, have been added to the school to accommodate the village's many children. Here again, we distribute our gifts. The children all wear pink school shirts, some of them torn and ragged. They assemble in disciplined order to mark the end of the school day, and sing together before running off in all directions. The path they take to and from school every day is an uphill climb over rocks and tree roots. Nowhere is the ground straightened, smoothed or paved. In this village, another of our students has an emotional meeting with her family. Many of us note an uncanny resemblance between our student and her cousin, one in a teenager's Western garb, the other in traditional Ethiopian dress.

At an elevation of 3,260 meters above sea level, Simien National Park is home to a unique population of gelada baboons, a species of Old World monkeys found only in the Ethiopian Highlands. A local guide gives us a lesson in "Baboonish" so that when we walk among them we understand when they are happy with our presence, and when they'd prefer we back away. We walk up rolling mountains and across grasslands, and at this altitude, the scenery of mountains, deep ravines and sheer cliff faces disappearing into the horizon is truly breathtaking.

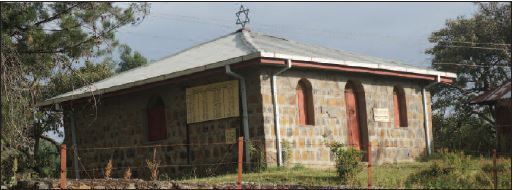

Back in the city of Gondar, we stroll through the market and our students excitedly sort through the traditional embroidered Ethiopian dresses, carefully choosing the right one for their mothers. The city of Gondar is also home to a large Bet Knesset of the Falashmura, the Ethiopian Jews who are still waiting to be allowed to make aliyah, while their Judaism is being contested. Behind its blue and white corrugated metal fence, the synagogue is a large open pavilion with long metal benches, and it is quite full, men on one side, women on the other. The service is partly in Hebrew and partly in Ge'ez, an ancient Ethiopian language used in their written scriptures. The women around us daven, they and the children all sing "Amen" at the appropriate times. The service ends with the entire congregation rising and singing Hatikva. We are in Africa, surrounded by people wrapped in their white Sabbath robes, and all of them, small children, men and women, are singing the words of Hatikva. Goose bumps and tears are the only reasonable response!

We leave pre-prepared suitcases of clothing for the Falashmura community. Two more of our students have meetings with relatives who live in the area of Gondar. No matter how minimalist their homes seem to us, it is taken for granted by them that they will host all twenty of our group. The buna coffee starts with the roasting of the beans, then grinding, brewing and serving in delicate coffee cups. Injira and cabbage salad also make an appearance. Our hosts are graciously welcoming.

Before leaving Gondar, we experience the route that our students' parents, and so many others, followed to get to Israel. We set out along a trail of loose stones where one could easily slide, rocks jutting out of the earth, dips, climbs, steep narrow passages. It wasn't easy, even in our sturdy sports shoes. And yet this was just one eight-hundredth of the path to Sudan that Ethiopian Jews travelled seeking a way of getting to Israel. And they did it in the dead of night, hiding by day. Nor did they have sturdy shoes, nor sometimes any shoes at all. We pass a child, no more than eight years old, wearing plastic sandals and carrying a load of sticks on his shoulder that are far longer than he is tall. He skips over the rocks, familiar to his feet. And I wonder how he would fare in the dead of night.

The last stop on our trip is to the more tourism-geared city of Bahir Dar on the shores of Lake Tana. We are informed that if Lake Tana were transported to Israel it would cover the country from the northern tip, across the Galilee, the Kinneret and Bet Shean, down to Haifa. Lake Tana is an important source of the Blue Nile, and we hike along rocky and occasionally steep paths to see the huge majestic waterfall that feeds it.

Our last day brings us back to Addis Ababa, where we visit the expansive compound of the Israeli Embassy. Here, at the site where he sat from morning to night, day after day, interviewing Ethiopian Jews and arranging their Aliya, Micha Feldman holds the group spellbound as he completes his story.

For the students on this journey, it was a delight to meet embracing family members, and to see whole families, a whole country, echoing their parents' traditions. They gained an appreciation of the beauty of the country, and its hardships, and of the very courageous journey their parents made. And I think they gained a more intense pride in their being Israeli. For me, the telling moment was when I asked if they were sorry their parents left this beautiful place, or if they would thank them, and their unequivocal answer was… "No, no, no, we thank them!"

And we thank ESRA for the initiative and the opportunity. *

*See more about ESRA's projects at: https://www.esra.org.il/projects.html

Photos: Mimi Tanaman, Eliran Moral, and Cynthia Yaakovi

Comments