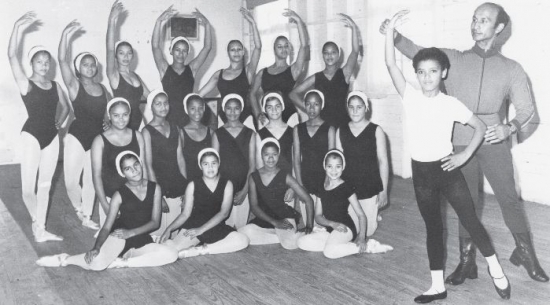

Gelvandale Toynbee Ballet

Many Jews in South Africa opposed the apartheid regime. My contribution was just a drop in the ocean. My story began in Cape Town where I was studying ballet at the University of Cape Town Ballet School. I was also working as a fashion model for leading fashion houses. After I married in 1961, we moved to Port Elizabeth where I began teaching ballet to white students for Masie Louden Carter who was a Royal Academy of Dance (RAD) ballet examiner.

During this time, I was approached by the Child Welfare service to run the Gelvandale Toynbee Ballet School. The school was in a colored (mixed race) township. I became involved with and committed to this school, training my students for RAD exams up to elementary level. Many times, there was rioting in the township and I would receive calls from my committee not to come. The ballet exam had to be conducted in their area - the students were not allowed to travel to the studio for whites even though their exam was the same as for the white students and they had the same examiner. I always prayed that the area would be quiet during these times.

This school achieved outstanding results which came to the notice of Dulcie Howes, doyen of the University of Cape Town Ballet School. My pianist, who lived in a retirement home, suggested that the talented students should perform there. That was the beginning of a whole transition for the ballet students. I had to get a permit for the students to perform in the retirement home. The residents were so appreciative that I made a commitment to try and bring the students to perform in other halls in Port Elizabeth. I wanted to make the public aware that people should be judged solely on talent, not on color.

I received many calls from the public for the dancers to perform in various halls in the city. Each time they were to perform, I had to apply to the Administration of Colored Affairs for a permit which imposed the following conditions: that no social mixing with the audience occurs; that the coloreds do not make use of any of the changing rooms or any other facilities provided for whites; and that they leave the premises immediately after their performance. (I have kept this humiliating relic of the apartheid era). If I received a permit which only allowed for the exact number of my dancers, then that would exclude the colored staff, particularly their drivers. To overcome this problem, because we had to strictly comply with the conditions of the permit, my husband Mark and I would drive backwards and forwards in our own cars collecting the students. The school was very proud to be asked to perform for Dr. Christiaan Barnard, the famous cardiac surgeon.

Dulcie Howes was very interested in the school and applied for a grant from Colored Affairs, as I was always fundraising for money for shoes and costumes. I was told that to show my commitment, I would have to raise a certain amount of money in order to receive this grant. To this end, I organized a Debutante's Ball, the first of its kind for colored people. This event took place in a colored area and the debutantes were presented to the town mayor. My late mother-in-law, Ada Dubb, then the Mayoress of Port Elizabeth, was a wonderful fundraiser and went around to business people in town asking them to contribute to an advertising brochure in support of the ballet school. Many of those donors now reside in Israel!

Teeth were always a problem with the students. For cultural reasons, many of the girls aged 16 would have their front tooth extracted. Of course this was detrimental to their appearance and I used to arrange for them to get professional dental advice. The school was examined every four months by Dulcie Howes, David Poole, principal dancer at the UCT Ballet School, and Johaan Mosaaval, a principal dancer at Covent Garden. These reports were sent in to the Colored Affairs Department. Some of the students would get bursaries to attend the UCT Ballet School, others would become teachers, and some went overseas to further their careers.

For 18 years I was active at the school and was nominated Woman of the Year for my contribution to the Gelvandale Toynbee Ballet School, before returning to Petersburg with my family.

Back in Petersburg, I became involved in helping with catering in the Jewish community while studying cooking, and I became a member of the South African Chef Association. A Dutch Reform Church organization called Woman Power that wanted to empower black women to receive improved salaries (they used to earn a pittance) approached me. I devised a program involving teaching cooking, baking, home management, first aid, hygiene and flower arrangements, and other subjects. Maids used to get up as early as 4 am in their townships in order to be at work by 7 am, and finished work late. Thousands of maids attended these courses during the ten years that I taught. Each course lasted three months. I invited chefs from Johannesburg to judge their work at the completion of each course, and they were also given oral exams. The certificates they received enabled them to improve their self-image and to receive better salaries. These courses, which were very popular, often appeared as news items on South African television news. A translator assisted me in Afrikaans and in the African language. Soon, black civil servants from other regions in South Africa, would come into my home in a clandestine way to learn etiquette (for example, how to lay a table and European habits). Many of my pupils were illiterate and many had never attended school. My recipes were taught using a wooden spoon or a hand beater as there were some employers who would not allow their maids to use their electric appliances!

Despite their limited resources, I was always amazed and proud of the high standard the students achieved at the completion of their course.

Doing something positive through my love of teaching ballet and cooking during the apartheid era was a very rewarding experience for me and my greatest joy.

Comments