This is the bread of our affliction?

Verse 21 of Psalms 118 - which has also been incorporated into the traditional song of praise and thanksgiving, Hallel - reads: "Odekha ki anitani, va-tehi li li-yeshua." This verse is usually translated as "I thank you [Lord] for answering me (ki anitani) and being my salvation." However, Midrash Tehilim ad loc. and several later sources understand the text as if it were written initani. The upshot of such a reading is that the verse is to be understood as "I thank you [Lord] because you have afflicted me and [thereby] have been my salvation." But how are we to understand gratitude for suffering?

The noted psychiatrist and specialist in substance abuse, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Twerski, in his Haggadah from Bondage to Freedom, writes that spiritual growth is not easy. [By spirituality, I believe Dr. Twerski means the ability to go beyond the demands of the body, towards some higher ideal.] "It calls for self-sacrifice and for denying oneself many of the things people consider to be the pleasures of life … People instinctively avoid pain and may avoid spiritual growth because of the discomfort it entails. But an addict has no choice: if he is to recover, he must improve the quality of his spirituality, otherwise he will relapse. This is why recovered addicts may be grateful for their suffering, because it was the only stimulus that could bring them to spirituality."

Allow me to suggest a slightly different approach which pivots on the conjunction ki, which in Hebrew has multiple meanings. It can sometimes mean "because", and this is how R. Twerski understands it above. But it can also mean "even though". Both meanings of ki appear in a single verse in Exodus 13:18: "When Pharaoh sent the people out, God did not lead them along the main road that runs through Philistine territory, even though that was the shortest route to the Promised Land (ki karov hu), because God said (ki amar elokim), 'If the people are faced with a battle, they might change their minds and return to Egypt.'" Hence, I would prefer to interpret this verse as: "I thank you [Lord], even though you have afflicted me, and for giving me the strength to survive and persevere."

Generally, no one willingly chooses suffering – even if it results in spiritual growth. This is analogous to the rabbinic dictum about the bee: "neither of your honey, nor of your stinger" (Midrash Tanhuma, Balak, sec. 6). In other words, I would forego your honey, if it means that I could forgo your sting. Nevertheless, life does not always give us choices. Those who have suffered have acquired a unique strength, a certain credibility that others lack. Having myself lost a child to cancer, I know that I can turn to grieving parents, testify about my loss and my life before and after, and tell them that if they will it, there is life after and notwithstanding death. Despite the gaping hole that forever remains, there is much good in life to live for – personal growth, family and community, vocation or avocation. The struggle to live with the pain is indeed worth it. Of course, it is not the life I would have chosen. But given that these are the cards I have been dealt, I thank the Creator for the strength to transmit the positive message to others.

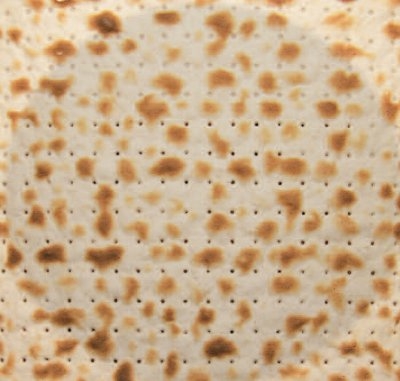

I'm sure that each of us has asked: Why did Hashem see it necessary to send us down to Egypt to be enslaved and suffer? Perhaps He felt that there were national lessons to be learned that could not be imparted in any other way. Many of the lessons of life are experiential. Indeed, the Egypt experience is the underlying rationale for more than fifty mitzvot and observances. I do know, however, that every Seder night we are obligated to re-experience the affliction and bitterness of the bondage and the exhilaration of the freedom. Every year we are required to become resensitized to the suffering of the downtrodden by eating matza and maror.

By reliving the Egypt experience yearly, we can transmit the moral, historical and national messages to the next generation in a more personal and, hence, credible fashion. Jews didn't choose to go down to Egypt to be enslaved. But in the process, we have learned a great many lessons that need to be transmitted to our children. And on Pesach night we can do so from a personal vantage point. That's what the Seder is all about.

Rabbi Dr. Aryeh A. Frimer is the Ethel and David Resnick Professor of Active Oxygen Chemistry at Bar Ilan University; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Comments