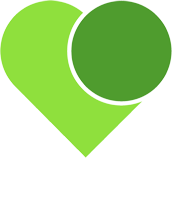

The Pierre Cardin Suit

My father, Yaacov Weitzman, in his Pierre Cardin suit with my mother, Naomi, at my daughter's wedding

He told me it was time to start packing up the apartment. He figured he had only a few weeks left. At most, maybe a couple of months.

He told me that age 95 would have been a good time to go. He could have done without these last three years, especially these last few months. He didn't like using a walker to get around even if he did refer to it as his red Cadillac. He especially didn't like being separated from my mother who had recently been moved to the nursing wing of their assisted living facility.

He didn't like being told not to go to the supermarket by himself, or, "Let Vera do the wash. Let Vera get the food from the dining room, that's what she's being paid for."

But he was stubborn.

I had rushed over from work earlier that morning after Vera had called, sounding desperate. "Your father's disappeared. I thought he was just taking a walk in the hallway."

I found him around the corner at Cafe Aroma, ensconced in a corner, practically horizontal, head reclining on the arm of the chair, legs perched on the seat of his walker. A half-eaten chocolate babka, his favorite pastry, sat on the plate. I gently touched his shoulder, "Abba, wake up!" Opening his eyes, he smiled up at me triumphantly. "You see, I can still manage."

Now back at his apartment, he pointed at his bookshelves, densely packed with photo albums, record albums, pottery collected on trips abroad, my mother's Shakespeare and Chaucer volumes mixed in with Fermat's Last Theorem and his other treasured mathematics and physics books. Then he gestured at the walls covered with framed photos documenting his and my mother's lives. Pictures of my father and his parents and siblings in Romania before they were expelled and banished to ghettos and slave camps. Pictures of my mother's family in Ukraine before the pogroms drove them to America. Pictures of the children and grandchildren, barmitzvah and wedding shots.

"Edie, I feel sorry for you. So much stuff. Oh boy, are you in for a job after I go! Getting rid of all of this. Maybe, start now with my clothes," he instructed. "See what can be given away."

I opened his closet and was immediately assaulted by the acrid smell of mothballs, a familiar odor from my childhood. There hung his black, pin-striped Pierre Cardin cashmere suit. What had possessed him to ship the suit to Israel when he moved back here in the last decade of his life? When could he possibly have worn it here? It's far too hot here for wool. It's far too hot for black. It's far too formal for most events, even for a wedding. No one in Israel dresses up. His legs now carried an extra 10 kilos of water weight, a byproduct of the congestive heart failure which had weakened him. Only sweatpants, several sizes too big, now fit. Clothes he would have scoffed at in the past.

At first, he seemed to agree that the suit could go but then he looked again, hesitating. "Wait, maybe let's keep it for now," he said. Wishful thinking on his part? Did he really think he might yet have an occasion to wear it?

He told me it was also time to start making arrangements about where he would be buried? When I began to cry, he hugged me. "It's okay. What's important is to enjoy every day. Enjoy Shira and Daniel. Enjoy your grandchildren." Advice he had tried to live by after surviving the Holocaust and the loss of most of his family who had been murdered in Bessarabia. "I welcome each day as if I were reborn," he often told me.

After his death three months later, I enlisted friends to help sort through the apartment contents. We made piles. Things to be discarded. Things to be donated. Things my children might want. Things I would keep.

The clothes were easy. They would go to charity. My son was too tall for any of them to fit even if still in style.

But when it came to the cashmere suit, I kept moving it from the give-away pile (who would ever want or need such a suit?) to the keep-for-me pile (maybe a grandson will end up being my father's size?).

In the end, I hung it in my basement closet. A year passed. For some reason, I decided to go through the pockets. A hot pink yarmulke inscribed Hallie, November 22, 2014 was buried in the inside jacket pocket. He must have saved it from his grand niece's bat mitzvah in Long Island. A clue as to when he had last worn the suit maybe. Curious, I was now on a mission to learn more. Where else had he worn the suit? I pored over family albums. Like most families, we tend to save photos that flatter. You certainly wouldn't find any pictures of my father at the end of the Holocaust, even if they once existed, when he weighed only 40 kilos - half of his original weight.

He often told me that he would have died were it not for the Ukrainian peasant woman who regularly fed him when he secretly left the confines of the Bershad ghetto to forage for anything remotely edible. One day, he woke up to find that his leg was paralyzed, and resigned himself to the fact that he would soon starve to death. Miraculously, the woman came looking for him, at great personal risk, managed to find him, and brought him two weeks' worth of food that enabled him to get back on his feet.

I'm sure that in those horrific days he never imagined that one day he would be attired in a Pierre Cardin suit.

Near the end of his life, he revealed that he had once stolen a piece of bread from a fellow Jew. He told me this as we sat in front of the lawyer who was drawing up a power of attorney document. I was appalled. But he simply said, "that's what you had to do to survive."

His survival was also thanks to eating garlic and onions. When I was young, he sometimes lost his temper if someone wasted food or accidentally spilled wine during the Sabbath blessing. For the rest of his life, he was obsessed with food. I can still hear his soft voice, speaking to me with his Romanian accent on his favorite subject.

"Edie, once you retire, let's go out to that new Romanian restaurant the cab driver told me about. He said they make a delicious mamaliga (a polenta-like dish)." And, "Edie, can you come over now? On your way pick up a pastrami sandwich for me from that place that just opened up. I hear they prepare it just like they do in Brooklyn."

I can still visualize his pale green eyes as he savored cold cuts, even though in his final months, he could only muster a bite or two. He dreamt of gourmet meals.

Turning the album's pages, searching for any signs of the Pierre Cardin suit, I find a quite dashing and dapper man in a winter coat and hat, fashionable in Tel Aviv in the late 1940s, even though he had not yet gained back all the weight he had lost during the War. He had exchanged money on the black market, which is how he could afford such clothes. Another image of a strapping athlete in neatly pressed white shorts, shirt, and knee socks, arm held up, tennis racket high in the air, about to execute a smashing serve. He had once made it to the quarter finals in a major tennis tournament held in Tel Aviv.

And finally, the suit! It's July 6th, 2011, my daughter's wedding day. He's wearing it proudly, along with a striped, cobalt blue silk tie. This is the suit's earliest appearance in the albums, three years before Hallie's bat mitzvah. My father often bragged about being able to wear clothing he had purchased years earlier without revealing their age because he kept them in mint condition. But my mother had probably insisted that he buy this Pierre Cardin suit for my daughter's wedding.

These days, almost three years after my father passed away, I rarely open the basement closet where the suit hangs. But occasionally when I do, I detect the faint smell of mothballs.

Edie Maddy-Weitzman was born in Tel Aviv in 1954, moved with her family to Brooklyn in 1958, and has been living in Ra'anana since 1981. She holds a doctoral degree in education from Boston University and a master's degree in clinical child psychology from Tel Aviv University. She was the high school counselor at the American International School for 35 years and is now retired.

Comments