The Land That Time Forgot

A funny thing happened on my way to Herzliya one day last August. The Number 29 bus on which I was riding somehow managed to collide with the back of a van on Ahuza Street in Raanana. The impact of the collision sent me flying through the air—yes, with the greatest of ease, landing me on the floor with a broken right leg. Following a brisk ride in an ambulance to a crowded emergency room, a battery of x-rays, the rude imposition of a plaster cast that seemed to weigh more than I do, days of hospitalization, surgery, and more hospitalization, I was sent home for months of virtual house arrest. Unable to put any weight on my slowly recovering "tibial plateau fracture", I sit at home alone for most of the day. The hours pass slowly. I try to fill them with reading, more reading, surfing the Internet, chatting with friends on Facebook, watching old TV shows on YouTube, watching new TV shows on Internet sites that pirate them, checking my email, and more reading. At other moments, I find myself disappearing into idle daydreams. I also catch myself revisiting incidents in my past, many of which I thought I had forgotten about—or wish I had.

The memory of one of these came to me today, unbidden, shortly after dawn, in one of those fleeting moments between really being asleep and actually being awake. It involved an attack of curiosity, a hike up a mountain, and a late afternoon visit with a bunch of people who may or may not really have been there. Let me explain.

In 1984 I had a newly minted Ph.D. in cultural anthropology from an Ivy League University, an academic expertise in the tribal peoples of Southeast Asia, two years of fieldwork experience in Indonesia, a doctoral dissertation that was soon to be published, the professional respect of my friends and colleagues, and no hopes of gainful employment whatsoever, anywhere or anytime in the foreseeable future. Had I been French and living in Paris in the 19th century, I would probably have joined the French Foreign Legion, to forget. But I was American, living in Philadelphia in the 1980s, so I did the next best thing. I took the streetcar downtown to 2nd and Chestnut Street, walked into the Federal Office Building and proceeded to join the United States Peace Corps.

After several months of my having to convince them that I wasn't just another out-of-work anthropologist trying to snag a free ticket back to the field for more career-enhancing research, the Peace Corps sent me straight to the Philippines, up into the mountains of the island of Mindoro and into the land of a remote and very traditional hill tribe known as the Hanuno'o.

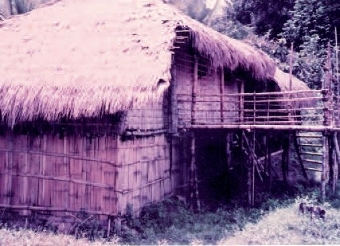

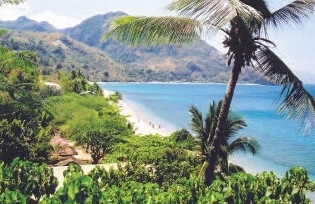

The Hanuno'o have a tradition that long, long ago they lived in big happy villages in the flat lowlands along the southeastern coast of Mindoro, right near the ocean. Unfortunately for anyone wanting to visit them, however, that ain't where they live now. Fear of being kidnapped and enslaved during the 18th and 19th centuries by Muslim "Moro" pirates from Mindanao drove their ancestors away from the coast and up into the mountains. That same fear of being grabbed, bound, thrown onto the deck of a pirate boat and spirited away to the Sulu Sea also made them spread out into widely dispersed little hamlets of no more than two or three closely related families, in little bamboo and grass houses built on stilts, hidden away on mountain tops and ridges, often invisible from a distance. As a result, the Hanuno'o who awaited my arrival in 1984 were often hard to get to and sometimes difficult to find.

But another result of their distance and relative isolation was that the Hanuno'o were well worth the effort of getting to and finding. They were, quite simply, every anthropologist's dream. Their traditional tribal culture was not only intact, but thriving. Their very appearance was magnificent, like something out of a travel book published a century-and-a-half ago. The men wore their hair long and tied up with colorful strips of native cloth. They wore loincloths and elaborately embroidered shirts with their own abstract designs. The even longer-haired women also wore those shirts, made from their own locally grown cotton, dyed blue with their own native indigo, and woven on their own native handlooms. Both sexes wore their own handmade bead necklaces and bracelets as well as metal bracelets made from their own piston bellow metal forges that they made from bamboo. And both men and women filed their teeth, which were constantly stained red from the almost incessant chewing of huge mouthfuls of betel nut, mixed with pepper leaf, lime powder, and tobacco.

The Hanuno'o grew one annual crop of rain-fed rice, high on the hillsides, which gave them plenty of time to maintain and enjoy their traditional culture, which included their rich oral poetry, recited to the music of their ancient native instruments, as well as their own native writing system, derived from ancient Sanskrit, that was still in daily use upon my arrival in 1984.

So…there I was. Living happily with the Hanuno'o. Day in, day out, clad in my loincloth, my arms festooned with bead bracelets, with bead necklaces dangling colorfully from my deeply suntanned neck. Contentedly spitting red jets of betel nut-colored saliva through heavily stained teeth, I wandered around the mountains from hamlet to scattered hamlet, and from house to little house, developing something that vaguely resembled a muscular physique, since no two steps in any direction ever seemed to be at the same level of altitude. Over there, you either go up or down.

Thus for three years I lived in a house the Hanuno'o put me in, at the end of a little hamlet called Dagum, overlooking a river called the Malang-og, high up in the hills of southern Mindoro. It was, in fact, while I was taking a bath and washing my loin cloth du jour in the Malang-og one afternoon that I happened to idly look up and notice a Hanuno'o house I had never seen before, way up on a hillside above me, almost at the top of the ridge.

Now, noticing houses you've never seen before is nothing out of the ordinary in that little corner of the world. The Hanuno'o, afraid of enemies from the past, like Moro pirates, as well as enemies of the present, like non-tribal land-grabbers, illegal loggers, and squatters from the lowlands, deliberately build their houses to be inconspicuous. One discovers a Hanuno'o dwelling serendipitously, by inadvertently looking in its general direction at just the right time of the day, when the sun hits it and makes its blond-brown cogon grass roof glow brightly in the sunlight for just a moment.

But I had been at Dagum for more than two years at this point, bathing and washing my clothes in the Malang-og every day, and had somehow never seen this dwelling before. When I asked my neighbors whose house that was, perched high up on the ridge above us, I received only blank stares or shrugged shoulders by way of reply. One or two people stated flatly that no one lived up there now.

The very next day, at precisely the same time and angle of sunlight, there I was. I was in perfect position to see the house again, but the house was somehow not in position to be seen by me — or for that matter, by anyone else. It simply wasn't there. It wasn't there again the following day, or the day after that, or ever again, no matter what time I came down to the river, or how often I looked up to find it.

Okay, I'm not what anyone would call a "normal person", but I do try occasionally to pass for one. So I decided to deal with this situation the way I imagined a "normal person" would: after a couple of weeks of not seeing the house again, I shrugged my shoulders, decided that no one lived up there now, and said, "To hell with it!"

Until I saw it again, around a half a year later.

I glanced up in its general direction — I swear it was inadvertent — and there it was, just like before, its light brown grass roof shining briefly in the afternoon sunlight. And I'll be damned if it wasn't there again the next day, and the day after that. Overcome with curiosity about a Hanuno'o house inhabited by Hanuno'o I had never met or seen before, and smart enough not to mention my sighting of the house to my Hanuno'o, who insisted that no such house existed, I finally said to myself, "Well hell, if this is going to bother you so damn much, why not just haul your sorry ass up there for a visit?" And so, around late morning on the following day, without telling anyone where I was going, up I went, sorry ass and all.

Hanuno'o-land, if I may call it that, is virtually criss-crossed with foot trails, most of them no wider than the average Hanuno'o, and almost all of them leading either straight up or straight down. I picked one I thought would take me up to the general vicinity of where I thought the house was, and started to climb. And climb.

Up I went, each footfall higher than the one before and lower than the next. The houses and gardens of my local Hanuno'o of Dagum slowly gave way to their rice swiddens which soon petered out into stretches of green fallow fields. These finally disappeared into forest that became thicker and darker as I got closer to the top. The little ribbon of a trail disappeared too, leaving me to pick my way slowly upward, through thorny wild plants and rocky underbrush. After a minute or two of more climbing and wondering what imp of the perverse had persuaded me to do this, I reached the top and what appeared to be a sunlit clearing a few meters ahead.

I heard them before I actually saw them. Some bits of indistinct conversation between what sounded like a man and a woman, some indistinct singing or chanting in a voice that I guessed belonged to a very old woman, and the familiar Hanuno'o sound of native rice being pounded with a traditional homemade wooden mortar and pestle. I stepped forward very slowly—using my famous, patented "weird-looking bearded white man approaching unknown group of Hanuno'o" walk—until I saw the house and the three people whose voices I had heard.

A middle-aged man and woman, whom I guessed to be husband and wife, were the ones pounding the rice. They stood on either side of the wooden mortar, alternately raising and plunging their club-like wooden pestles down into the mortal bowl full of unhusked rice. An old woman was sitting some distance away, winnowing the newly husked rice in a homemade tray fashioned from woven strips of rattan. Both the winnowing tray and the mortar-and-pestle combo appeared to be very old, worn and darkened by use and time. The old lady was indeed singing, if one could call it that, intoning a bit of Hanuno'o oral poetry in a style and cadence I had never heard before. The whole scene looked like something out of a diorama in a museum of ethnology.

As I got closer, they saw me. The couple stopped their rice-pounding, the old lady stopped winnowing and chanting. All three became motionless and stared at me with an unfriendly silence that literally chilled me. I smiled, even bowed, and began to introduce myself, softly speaking my best Hanuno'o in my most diffident tone of voice. After what seemed like several years, the man quietly told me that they were aware of who I was and knew where I lived. When I asked why I'd never see them before, the woman said that they never go down to the river or mix with the Hanuno'o who live there. The old lady stared at me intently as the man repeated, "Never."

The man and woman glanced at each other for a moment, and seemed to have come wordlessly to some sort of decision. The three of them then told me their names—I will not write them here now, or ever—and motioned for me to join them inside the house.

Hanuno'o houses are what most people would call "primitive", with bamboo floors and walls, cogon grass roofs, and built on wooden stilts. They are almost always sturdy and well-made, and kept scrupulously clean and tidy. The house I was ushered into now, however, was dirty and, if not dilapidated, noticeably unkempt. There were gaping holes in the grass roof that no doubt let in copious amounts of rain. Many of the bamboo floor slats were broken as well, forcing me to sit down carefully and avoid moving around. As if that weren't enough, the walls appeared to be blackened, perhaps by fire, as though the house had once been partially burnt and never repaired.

No sooner was I seated and settled than four more people turned up - two young women, one old man, and a girl who appeared to be around nine or ten years of age—the only child I was to see that day. I asked if there were other houses and people up this way, and the middle-aged man darted his eyes around quickly at the others before finally saying that there were. And then no one said anything else.

I introduced myself to the newcomers. They stared at me for a while and then told me their names. I asked for a drink of water. The old man motioned to one of the young women to go out and get me some. She returned a moment later, handing me an age-darkened bamboo cup full of water from a nearby spring. I reached for my little rattan basket and brought out betel nut, which they all requested, grabbed, and fervently began to chew.

And as they chewed, murmuring in low voices to each other, I watched them and was struck by how out-of-the-way and off-the-beaten-track these people appeared. I mean, they looked like Hanuno'o certainly enough. If anything, they looked somehow "more Hanuno'o" than any of the Hanuno'o I knew and dealt with every day. And that is what grabbed my attention.

My Hanuno'o neighbors and friends were traditional, but they went down to the lowlands occasionally, where they worked a bit for lowlanders, made miniscule amounts of money, and bought things from markets in lowland towns. Some had sporadic contact with traders, missionaries and government officials; others had already begun to send their children to missionary-run elementary schools, while a few even made their way to local town hospitals when they were very, very sick. A number of the younger people had simple, battery-powered portable radios, and many were already eating their native Hanuno'o rice off plastic dishes instead of banana leaves, and drinking their pure spring water out of discarded Cal-Tex plastic motor oil containers instead of hollowed-out coconut shells.

But the people I was sitting with now seemed to be dwelling in a proverbial Land that Time Forgot. As much as I glanced around—and I glanced around a lot that day—I could find nothing that wasn't authentically, traditionally Hanuno'o. For example, while all of the Hanuno'o I knew wore abundant bead necklaces, they were always made from plastic beads, mass-produced and imported to the Philippines from somewhere in China. The beads in these peoples' necklaces were made of polished stone which I had seen only around the necks of a few very old men and women in the black and white photographs of very old books, and once in a museum. Indeed all of their possessions were native, traditional to the point of being historic, and heavily darkened by the passage of time.

And while my command of spoken Hanuno'o was reasonably good, I found that I could barely follow these people's conversations to save my life. The cadence of their speech was somehow different from what I was familiar with, and they were using words and expressions I had never heard before. It seemed that I had stumbled upon an isolated, virtually forgotten and culturally untouched group of Hanuno'o. What anthropologist could have asked for anything more?

The hours passed, and the afternoon sunlight began slowly to wane. The two young women and small girl drifted away, leaving the older people behind with me. As the first shadows began to appear on the hillside, the middle aged man took a very deep breath, looked down at the broken bamboo floor, and told me I should begin to head home before it got too dark. I smiled, thankful for his concern that the trip through the rocky underbrush might be hazardous in the dark. But as I reached into my basket for more betel nut to offer them, the man raised his head, looked at me sharply, and in an unmistakable tone of warning told me I had to leave at once.

So leave I did, carefully making my way downwards through the lengthening shadows, until I finally found myself on a more or less clearly visible trail. I reached Dagum a little after nightfall, greeted with relief by neighbors who had spent the afternoon wondering where the hell I'd wandered off to.

My audience became hushed and quickly grew larger as I happily began to tell them where I had gone and with whom I had been. It may be a cliché, but I actually saw their complexions go white as the blood drained from their faces while I repeated the names of the people I had met. I was asked—ordered, in fact—to relate again and again the precise route I had taken to get where I said I had gone. I was told to recount, over and over again, exactly what I'd seen and heard. I was questioned, with evident alarm, whether I had eaten anything while I was up there. And I watched them almost recoil when I told them how I was warned to leave before night began to fall.

After a moment that seemed so quiet I imagined I could hear the earth rotating on its axis, Dagum's headman cleared his throat and said, "Carl, those people are from the time of my grandparents. They were some of our people who were killed during the big fiery war the Japanese fought here long ago against your people, the Americans." He let that message sink in before concluding, "Carl, you have been with ghosts."

Well, do I believe I spent an afternoon almost 30 years ago with a bunch of Hanuno'o ghosts? Do I believe that unhappy spirits with unresolved issues continue to haunt the places where once they lived? Of course not.

I might add, however, that I never saw that house again—not at any time of the day, or at any season of the year. And, if the three odd decades that have passed between that day and now have taught me anything at all, it is that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy, psychology, or even anthropology.

Comments