The Castel - National Heritage Site

A dusty, twisting and turning path – the bushes and weeds on either side beginning to wilt as the summer heat beats down – leads up to a mountain top in the western Jerusalem Hills, and almost immediately turns the clock back 73 years.

The summit of Mount Maoz stands 790 meters above sea level, enabling incredible views in all directions.However, 73 years ago, none of the embattled Jews or Arabs would have had the opportunity to absorb the view as they kept their heads down low in the protective narrow trenches hacked out of the hard rock and solid ground of the mountain.

During the winter of 1947-1948, Jewish soldiers fought here in some of the bitterest battles, as they engaged the Arab forces in control of the Castel – a thick stone-walled fortress on top of Maoz. Conquering this fortress was imperative to securing the narrow pass through the Jerusalem hills on the main Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway below. Approximately 100,000 Jews – around one-fifth of the Jewish population of the Yishuv at the time – lived in the besieged city of Jerusalem and environs. They were all totally dependent on life-sustaining supplies being brought in from the coastal plain, as all other access roads to the city were under the control of Arab forces. Scores of Jewish and Arabs soldiers died in these battles, as the Palmach tried to wrest control of the Castel from the Arabs, thereby releasing the enemy stranglehold on the main artery leading upward to the physically, emotionally and spiritually elevated city of Jerusalem.

A visit to the Castel hilltop in present times truly brings home not only the importance of the outcome of that crucially important battle but also how against all odds Jewish fighters eventually won that battle for control of the Arabs heavily fortified hilltop above them and the huge price paid in human life.

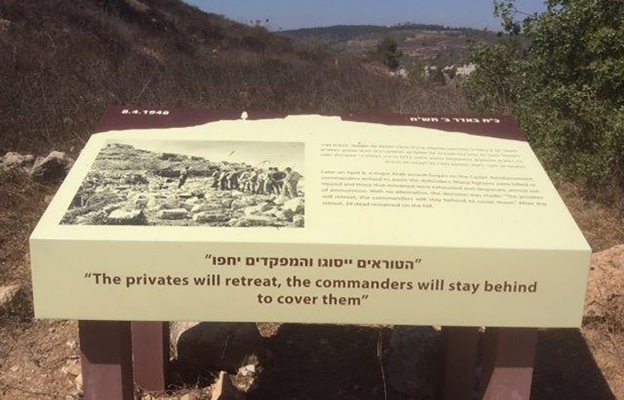

In recent years, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority developed the Castel National Heritage Site. They have created an impressive literal hands and feet on experience commemorating the fighting, and particularly the pivotal battle that eventually ousted the Arabs. Visitors are offered a truly in-depth and much-appreciated understanding of that crucial victory on Mount Maoz, thought by some to be Mount Ephron, the biblical border between Judah and Benjamin (Joshua 15.9). On the lower slopes, in a circular covered sitting area, short black-and-white films of the fighting back in those desperate days are screened. The visual and audio material radiates strong educational messages, highlighting the values set forth during that on-site combat of 1948 – the comradeship, determination, leadership and trust. A number of strategically covered resting places with mind-boggling views are dotted along the upward trail, as are attractive flatbed information boards full of historical text and sepia photos taken during the actual action.The boards incorporate detailed descriptions of the fighting – creating for the visitor a true blast-to-the-past experience, as well as point-by-point explanations and clear mapping of the incredible views along the trail.

Among the Arab fatalities was a member of one of Jerusalem's most prominent and highly esteemed Arab families, the al-Husseinis. Commander Abed Kadar al-Husseini, a much revered leader who had studied chemistry in Lebanon, participated in the Arab revolt against the British before escaping to Iraq where he continued to work against the British. Whilst away from the Middle East, he also spent time in Nazi Germany where he became an expert in explosives prior to his secret return to British Mandatory Palestine, where he became commander of an army created by the Arab Higher Committee.Al-Husseini, and a few of his fellow commanders, unwittingly walked into an area being held by Jewish soldiers; he was shot dead, but his deputy and adjutant managed to escape back to tell the tale.

It is only a short drive from the Castel to the cemetery at Kiryat Anavim – the first kibbutz, founded in the 1920s, in the Judean Hills.Part of the cemetery is for kibbutz members, but higher up a small hill are row after row of military graves; the vast majority of these graves are of young men who died fighting in Israel's War of Independence. Visiting the cemetery, after having been at the Castel National Heritage Site just a short time beforehand, is heart-wrenching.Walking along the neatly paved paths between rows of white stone with gold lettered military graves, the emblem of the IDF on each top-right-hand corner, you feel the enormity of the loss of so many young men and women; the eerie silence hanging heavily over the cemetery is truly deafening.

On the grave of Yaacov Levy someone has placed a black and white head-and-shoulders photograph of the dark-haired, handsome young man.The photograph covers a third of the fighter's gravestone, held in place by a large stone, with a smaller stone – left as a mark of remembrance – perched above alongside the IDF emblem. Yaacov Levy was aged just 15 when he died serving his country in war, a fact that stunned this writer whose eldest of twelve grandchildren is exactly that age, a bashful, pimples-and-all teen with hardly a care in the world.

A local guide explained about one of the graves higher up from Yaacov Levy's, close to a neatly clipped lawn with wooden benches shaded by enormous trees. There an oblisk-shaped memorial sits on a small hill towering above the rows of graves, a channel of water gently flowing downhill. The grave he pointed out belongs to Aharon Jimmy Schmidt, a 22 year-old Palmach company commander who died toward the end of the war on a hilly ridge at the entrance to the Judean Hills, today the city of Beit Shemesh. Jimmy's Russian born father, Menachem Shemi Schmidt, who in the early 1940s had served in the British Army,was an artist and sculptor.He was told by a close friend and fellow soldier of his fallen son that, when they had been at the Kiryat Anavim cemetery, Jimmy had commented that after the war he would ask his father to design a memorial to "the cream of our youth" buried there.Acting on the words of his son, Menachem Shemi Schmidt created the abstract stone block memorial describing it as "a cry of distress at the terrible injustice of life having been severed in the prime of youth". When he died in 1951, Menachem Shemi Schmidt, was buried in the same cemetery as his beloved son Jimmy – both at rest in the arms of long cast shadows created by the memorial on the hill.

Comments