Magna Carta: The Jewish Connection

On June 15, 2015, England and many other English-speaking countries will celebrate the eighth centenary of one of the most important historical documents of the Western World: namely "Magna Carta Libertatum", usually shortened to just "Magna Carta" (Great Charter of Liberties) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magna_Carta. It is specifically England rather than Great Britain or the United Kingdom, because these latter entities did not exist in 1215, only coming into being in 1707 and 1801 respectively.

The lavish festivities are being financed by funding from the National Lottery and include media programs, books and events for this landmark occasion. Postage stamps and a coin (which, however, erroneously shows King John signing with a quill pen instead of impressing his signet ring into wax) have been issued.

So what exactly is being celebrated?

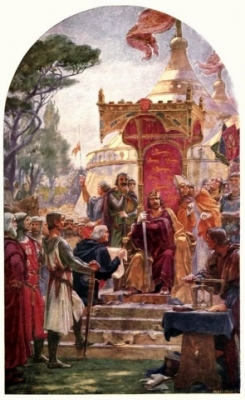

On that date (according to the Old Style Calendar) in 1215, in a water meadow named Runnymede alongside the River Thames near Windsor, and under the auspices of the Archbishop of Canterbury, England's senior cleric, King John reluctantly met up with his powerful but recalcitrant feudal barons. They were rather less than pleased with their king who had led them to defeat against the French at the Battle of Bouvines, which had resulted in the loss of many of the barons' French possessions.

In addition, John's autocratic and arbitrary rule was beginning to verge on tyranny. The barons presented the king with a number of demands, which was ground-breaking at a time when the natural order of things was that monarchs ruled by Divine Right, a doctrine that enjoyed the backing of the Church. It was the sovereign who made known his requirements from his subjects and not the other way about. The barons, however, saw their action as nothing less than the forging of a new relationship between the king and his people, or at least its upper stratum.

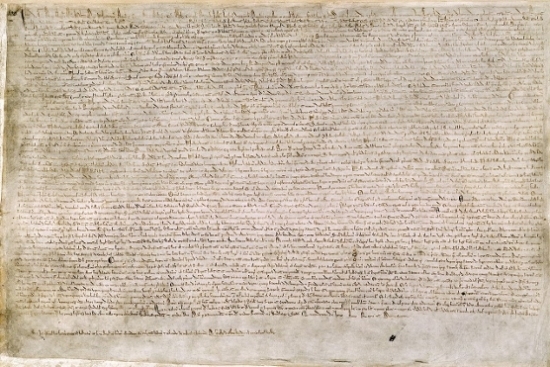

The document itself contained some 3,500 words in Latin and was written on calfskin. It was not, at the time of its writing, divided into separate clauses (the clause numbering system, giving a total of 63 clauses, in use today was only devised in 1759). The charter required John to proclaim certain liberties and to renounce the use of arbitrary power. The precepts of the charter were to be administered by 25 neutral barons.

Much of this is well-known, but what is perhaps less so is that among the clauses are two that specifically refer to Jews, and these became clauses 10 and 11. Clause 10 states (in modern English): "If anyone who has borrowed money from the Jews, any sum, great or small, die before the loan be repaid, the debt shall not bear interest so long as the heir is under-aged, whosoever tenant he be and if that debt fall into our hand (i.e. the king) we will not take anything except the principal sum contained in the agreement."

Clause 11 says: "And if anyone die owing a debt to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and pay nothing of that debt; if the dead man leave children under age, they shall be provided with necessaries in keeping with the holding of the deceased and the debt shall be paid out of the revenue, reserving however service due to overlords; and debts owing to others than Jews shall be dealt with in the same manner."

There is circumstantial evidence that there were Jews serving in the Roman Army in the province of Britannia, but it was not until 1070 that we have any written records of organized Jewish life in England. Jews had originally been invited over from Rouen, part of his French possessions, by King William I, known as the Conqueror, four years after the Norman Conquest of 1066. William's purpose for their admittance was to provide finance for the king's projects and to boost trade in his new possessions. William knew that these Jews had wide European connections as they had been living there for 1,000 years and, crucially, had access to capital.

Christians were forbidden by Canon Law to lend money at interest, a practice known as "usury". As non-Christians, Jews were not subject to Canon Law and were only forbidden by Jewish Law from exacting interest from other Jews. They thus served a useful purpose in providing finance for an expanding economy. Money-lending was one of the few professions open to Jews, who were forbidden to own land and debarred from the trade guilds, entry to which required them to take a Christian oath.

They were, however, liable to heavy taxation and monetary confiscations on flimsy excuses whenever the king needed money, a fairly frequent occurrence. This was by no means the first legal document in medieval England to mention Jews as there is a wealth of such documentation in the Public Record Office at Kew in London. Because they were such a revenue-producing asset, Henry I, who was the fourth son of the Conqueror and reigned from 1100-1135, deemed it expedient to put "his" Jews (they were officially Crown property) onto a proper legal footing. He issued a Royal Charter of the Jews, and its seven clauses became the template for all subsequent versions of this document.

Although King John set his seal to Magna Carta, it did not last long and was soon annulled by Pope Innocent III. When John died a year later, his son Henry III was still a minor so the government appointed William Marshal, the 1st. Earl of Pembroke, as his regent. The government reissued a watered-down version of the document in a bid to get the barons onside. This later version did not make any mention of Jews, as these references were considered prejudicial to the Exchequer, nor did they appear in any of the further reissues.

Each monarch reissued the charter, although as the English Parliament grew in power its practical importance diminished. Its principles were raised at crucial points in English history, such as the English Civil Wars of 1642-49 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It also greatly influenced the American colonists and subsequently the United States Constitution, which is why the memorial at Runnymede was erected in 1957 by the American Bar Association.

Of the original thirteen copies of the 1215 document, four survive. Two are in the British Library and one each is in Lincoln and Salisbury Cathedrals. Of these four, only the one in the British Library has the Great Seal of England still attached, although it is fire-damaged. The size and text of all four differ slightly from one another. Various copies of later versions are in existence, including one from 1297 in the National Archives of the United States in Washington DC.

Only three clauses of Magna Carta remain on the statute book of the United Kingdom today. These refer to the ancient liberties of the Church of England, those of the City of London, and the right to due process of law for all citizens charged with a crime. (Israel inherited some provisions of English Law from the Mandate period.)

As for the Jews of medieval England, after their 220-year sojourn in the kingdom they were expelled in 1290 by King Edward I. The Statute of Jewry, passed in 1275, forbade Jews to lend money at interest and this reduced the community to small-time peddling. Some money-lending however did continue clandestinely or under the guise of trade deals, but this was very dangerous and could lead to the death penalty. In addition, heavy taxation and confiscations had taken their toll so that England's Jews had simply outlived their usefulness, and the king knew that his expulsion decision would be popular with both people and Church. The Edict of Expulsion was one of Royal Prerogative and was proclaimed on July 18, 1290, which just happened to be Tisha B'Av. This gave the estimated 2,500-5,000 members of the Jewish community until the Christian holy day of All Saints (November 1) to quit the realm. Officially, at least, there were then no Jews in England for 366 years.

There was never a formal "re-admittance" of Jews into England. However, such a plea to the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, during the English Commonwealth was submitted by Rabbi Menassah ben Israel of Amsterdam. This was debated in the Council of State but no firm conclusion was reached. Intriguingly, the record of deliberations on that request has been torn from the Council's minutes' book by person or persons unknown. So Jews already living there simply "came-out". No Act of Parliament was required as the 1290 expulsion had been ordered by the king, not Parliament, and only affected those Jews living in England at that time.

Magna Carta has profoundly influenced Western thought and culture and is being rightly commemorated this summer in the English-speaking world. Hebrew Scripture, through its adoption by the Christian Church, is inextricably woven into this thought and culture. This, together with the important role played by the numerically small but highly significant Jewish population of medieval England, provide an indelible connection with the long history of the Jewish people.

Comments