Legacy of the Man Who Created Fiddler

Sholem Aleichem ... a founding father of modern Yiddish literature

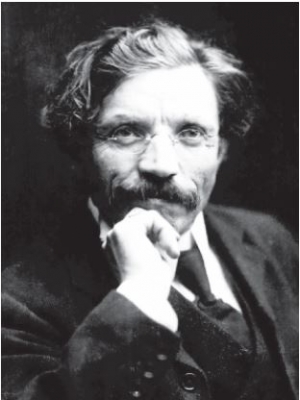

Not many people will recognize the name Solomon Naumovich Rabinovitz when they hear it. But, if they hear the name Sholem Aleichem, everyone will recognize one of the founding fathers of modern Yiddish literature. A supreme Jewish humorist, Sholem Aleichem tapped into the energies of the East European, spoken-Yiddish idiom and invented modern Jewish archetypes, myths, and fables of unequaled imaginative potency and universal appeal.

Sholem Aleichem was born 160 years ago, in the year 1859 in Pereyaslav in the Ukraine, and moved as a child with his family to Voronkov, a neighboring small town which later served as the model for the fictitious town of Kasrilevke, described in his works.

Sholem Aleichem received his early education in a traditional cheder in Voronkov. His father, a wealthy merchant, was interested in the Haskalah (Enlightenment) and in modern Hebrew literature. A failed business affair caused the family to move again. Days of poverty and want followed, and in 1872 his mother died of cholera. In 1873, at the age of 14, he entered a Russian gymnasium from which he graduated in 1876.

Though he began writing in Hebrew, his first "serious work" – a dictionary of the curses employed by stepmothers – was written in Yiddish. Later, he wrote Hebrew biblical "romances" similar in style to those of Abraham Mapu, of which his father was particularly fond.

In 1877, he became a tutor for the children of a prominent estate owner, Elimelekh Loyev, remaining there for three years until a love affair between him and Olga Loyev, Elimelekh's daughter, was exposed. Brokenhearted but unvanquished, he ran for the elected post of crown rabbi (see panel below) of the town of Lubny (Yid., Luben), won the elections, and lived there from 1880 to 1883.

In 1879 he began publishing. For about three years he wrote reports and articles, mostly about Jewish education, for two Hebrew publications.

In 1883, Solomon Rabinovitz married Olga, and decided to write in Yiddish rather than in Hebrew. One of his first stories appeared in a Yiddish paper under the pseudonym "Sholem Aleichem," which in Hebrew means "Peace be unto you." From this time on, this became his pen name.

He explained the pseudonym as a guise to conceal his identity from his relatives, especially his father, who loved Hebrew. In those days Yiddish literature was greatly despised by the maskilim (enlightened) who wrote in Hebrew and the Jewish intelligentsia in Russia who spoke Russian, and this led Yiddish authors to write under pseudonyms or to publish their works anonymously.

He wrote stories, sketches, critical reviews, plays, and poems in both verse and prose. Sholem Aleichem did not limit his creative scope to Yiddish, but published stories, sketches, and articles in Hebrew and in Russian.

In 1888, when he inherited his father-in-law's estate, his financial situation enabled him to realize a long-cherished dream: the founding of a Yiddish literary annual through which the standards of European taste would be introduced into Yiddish literature.

Following a pogrom in 1905, the family crossed the border and ensconced itself in Lemberg (today Lviv / Lvov). The following summer he went through Geneva to London where he spent part of the fall before sailing for New York City.

In New York the Yiddish and the American-English press greeted Sholem Aleichem as a celebrity. Dubbed the "Jewish Mark Twain," the journalistic fanfare went to his head. Sholem Aleichem, insensitive to the New York Yiddish literary community's strong sense of its own worth, made patronizing remarks, announcing the role he would play in elevating the American Yiddish theater to the European artistic level.

This boasting came home to roost as Sholem Aleichem's own two plays, Yaknehoz and a dramatization of Stempenyu, were flops – much to the schadenfreude of the local Yiddishist community. Compounding his unpopularity, Sholem Aleichem alienated the influential left-wing Yiddish press by aligning himself with conservative and traditionalist newspapers such as the Tageblat. In short, his American sojourn turned out to be a fiasco. In the summer of 1907 he departed for Europe, disappointed and resentful.

Unwilling to return to the Tsarist empire, he stayed briefly in Geneva, then went to Berlin. Crestfallen and fatigued, Sholem Aleichem nevertheless had to produce at a steady pace if he was to earn an income.

In 1908 financial hardship and nostalgia for his East European readers drove Sholem Aleichem to tour throughout the Jewish Pale of Ukraine and Belorussia. For three months he traveled from one town to another, performing as a one-man act, which took a serious toll on his health.

Friends purchased the rights to his entire published corpus and presented them to him on his twenty-fifth anniversary as a Yiddish writer. This enabled him to publish an extensive edition of his collected works, which yielded a certain dependable annual income.

During World War I Sholem Aleichem escaped from Berlin to Copenhagen. In 1914, in poor health and cut off from his sources of income, he returned to New York. There he signed a contract with the newspaper Der Tog, which assured him a fixed income, and he returned to habitually producing both large and small-scale literary projects.

What is not so well-known is that when he and several other family members applied for visas to return to the United States, every family member was approved except his son Michel (Misha), who suffered from a severe case of tuberculosis. When the rest of the family returned to New York, Misha was left alone in Copenhagen.

Misha became severely depressed and finally, in the summer of 1915, took the ferry from Copenhagen to Malmö, Sweden and committed suicide by jumping off the boat in the middle of journey. Since the ferry was on its way to Sweden, he was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Malmö.

Crushed by the news of his son Misha's sudden death, Sholem Aleichem wrote a will and spoke of his own impending death. He nevertheless continued writing new chapters for the autobiographical novel. In 1916 he fell ill and died on May 13. Two days later he was given a temporary burial, but was reburied in the Har Carmel cemetery in Queens, although he desired to be buried in Kiev alongside his father.

The funeral was one of the largest at the time, attended by over 100,000 mourners. His ethical will, a masterpiece in itself, was published in its entirety in the New York Times and was read into the Congressional Records.

His immense popularity did not decline after his death but rather increased beyond the Yiddish-speaking public. In 1910 his son-in-law, Hebrew author Y. D. Berkowitz, began translating his works into Hebrew.

His works have also been translated into most European languages, as well as Russian and English. His plays and dramatic versions of his stories have been performed by the best Yiddish and Hebrew theatrical companies in America, Israel, Russia, Poland, and many other countries.

The dramatic version of Tevye's Daughters has been performed by the finest Yiddish actors, and in the 1960s these sketches formed the basis of the stage and film musical, Fiddler on the Roof.

Crown Rabbis: The crown rabbis of late imperial Russia held the government-mandated designation of rabbi, but their functions as record keepers, Russian administrative representatives, and sometimes Jewish communal (but secular) leaders belied the religious title. The roots of the crown rabbinate lay in Tsar Alexander I's decrees of the 1820s requiring rabbis to maintain Jewish population registers in Russian as well as Hebrew.

Sholem Aleichem even penned his own epitaph

English translation from Yiddish

Here lies a plain and simple Jew

Who wrote in plain and simple prose;

Wrote humor for the common folk

To help them forget their woes

He scoffed at life and mocked the world,

At all its foibles he poked fun

The world went on its merry way,

And left him stricken and undone.

And while his grateful readers laughed,

Forgetting troubles of their own,

Midst their applause – God only knows –

He wept in secret and alone.

Bel Kaufman, Sholem Aleichem's granddaughter

Yiddish transliteration

Do ligt a yid a posheter

Geshriben Yidish-Taytsh far vayber

Un far'n prosten folk hot er

Geven a humorist, a shrayber

Dos gantse lebn oysgelakht

Geshlogn mit der velt kapores

De gantse velt hot gut gemakht

Un er–oy vey–geven af tsoris.

Un davke demolt ven der oylem hot

Gelakht, geklatsht un fleg zikh freyen

Hot er gekrenkt–dos veyst nor Got

B'sod, az keyner zol nit zeyn.

Acknowledgements: Many of the facts in this article are based on information on the websites www.Jewishvirtuallibrary.org/shalom-aleichem and www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Sholem_Aleichem

Comments